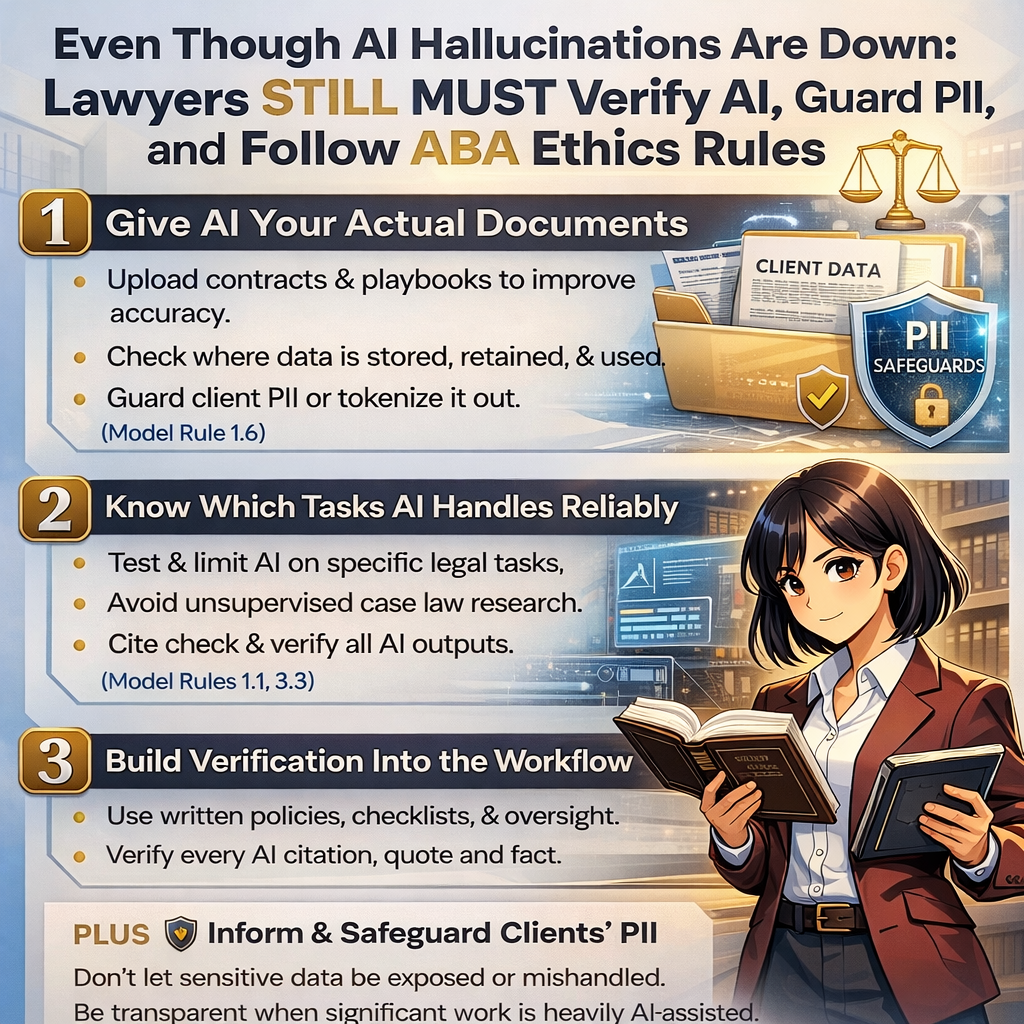

MTC: Even Though AI Hallucinations Are Down: Lawyers STILL MUST Verify AI, Guard PII, and Follow ABA Ethics Rules ⚖️🤖

/A Tech-Savvy Lawyer MUST REVIEW AI-Generated Legal Documents

AI hallucinations are reportedly down across many domains. Still, previous podcast guest Dorna Moini is right to warn that legal remains the unnerving exception—and that is where our professional duties truly begin, not end. Her article, “AI hallucinations are down 96%. Legal is the exception,” helpfully shifts the conversation from “AI is bad at law” to “lawyers must change how they use AI,” yet from the perspective of ethics and risk management, we need to push her three recommendations much further. This is not only a product‑design problem; it is a competence, confidentiality, and candor problem under the ABA Model Rules. ⚖️🤖

Her first point—“give AI your actual documents”—is directionally sound. When we anchor AI in contracts, playbooks, and internal standards, we move from free‑floating prediction to something closer to reading comprehension, and hallucinations usually fall. That is a genuine improvement, and Moini is right to emphasize it. But as soon as we start uploading real matter files, we are squarely inside Model Rule 1.6 territory: confidential information, privileged communications, trade secrets, and dense pockets of personally identifiable information. The article treats document‑grounding primarily as an accuracy-and-reliability upgrade, but lawyers and the legal profession must insist that it is first and foremost a data‑governance decision.

Before a single contract is uploaded, a lawyer must know where that data is stored, who can access it, how long it is retained, whether it is used to train shared models, and whether any cross‑border transfers could complicate privilege or regulatory compliance. That analysis should involve not just IT, but also risk management and, in many cases, outside vendors. “Give AI your actual documents” is safe only if your chosen platform offers strict access controls, clear no‑training guarantees, encryption in transit and at rest, and, ideally, firm‑controlled or on‑premise storage. Otherwise, you may be trading a marginal reduction in hallucinations for a major confidentiality incident or regulatory investigation. In other words, feeding AI your documents can be a smart move, but only after you read the terms, negotiate the data protection, and strip or tokenize unnecessary PII. 🔐

LawyerS NEED TO MONITOR AI Data Security and PII Compliance POLICIES OF THE AI PLATFORMS THEY USE IN THEIR LEGAL WORK.

Moini’s second point—“know which tasks your tool handles reliably”—is also excellent as far as it goes. Document‑grounded summarization, clause extraction, and playbook‑based redlines are indeed safer than open‑ended legal research, and she correctly notes that open‑ended research still demands heavy human verification. Reliability, however, cannot be left to vendor assurances, product marketing, or a single eye‑opening demo. For purposes of Model Rule 1.1 (competence) and 1.3 (diligence), the relevant question is not “Does this tool look impressive?” but “Have we independently tested it, in our own environment, on tasks that reflect our real matters?”

A counterpoint is that reliability has to be measured, not assumed. Firms should sandbox these tools on closed matters, compare AI outputs with known correct answers, and have experienced lawyers systematically review where the system fails. Certain categories of work—final cites in court filings, complex choice‑of‑law questions, nuanced procedural traps—should remain categorically off‑limits to unsupervised AI, because a hallucinated case there is not just an internal mistake; it can rise to misrepresentation to the court under Model Rule 3.3. Knowing what your tool does well is only half of the equation; you must also draw bright, documented lines around what it may never do without human review. 🧪

Her third point—“build verification into the workflow”—is where the article most clearly aligns with emerging ethics guidance from courts and bars, and it deserves strong validation. Judges are already sanctioning lawyers who submit AI‑fabricated authorities, and bar regulators are openly signaling that “the AI did it” will not excuse a lack of diligence. Verification, though, cannot remain an informal suggestion reserved for conscientious partners. It has to become a systematic, auditable process that satisfies the supervisory expectations in Model Rules 5.1 and 5.3.

That means written policies, checklists, training sessions, and oversight. Associates and staff should receive simple, non‑negotiable rules:

✅ Every citation generated with AI must be independently confirmed in a trusted legal research system;

✅ Every quoted passage must be checked against the original source;

✅ Every factual assertion must be tied back to the record.

Supervising attorneys must periodically spot‑check AI‑assisted work for compliance with those rules. Moini is right that verification matters; the editorial extension is that verification must be embedded into the culture and procedures of the firm. It should be as routine as a conflict check.

Stepping back from her three‑point framework, the broader thesis—that legal hallucinations can be tamed by better tooling and smarter usage—is persuasive, but incomplete. Even as hallucination rates fall, our exposure is rising because more lawyers are quietly experimenting with AI on live matters. Model Rule 1.4 on communication reminds us that, in some contexts, clients may be entitled to know when significant aspects of their work product are generated or heavily assisted by AI, especially when it impacts cost, speed, or risk. Model Rule 1.2 on scope of representation looms in the background as we redesign workflows: shifting routine drafting to machines does not narrow the lawyer’s ultimate responsibility for the outcome.

Attorney must verify ai-generated Case Law

For practitioners with limited to moderate technology skills, the practical takeaway should be both empowering and sobering. Moini’s article offers a pragmatic starting structure—ground AI in your documents, match tasks to tools, and verify diligently. But you must layer ABA‑informed safeguards on top: treat every AI term of service as a potential ethics document; never drop client names, medical histories, addresses, Social Security numbers, or other PII into systems whose data‑handling you do not fully understand; and assume that regulators may someday scrutinize how your firm uses AI. Every AI‑assisted output must be reviewed line by line.

Legal AI is no longer optional, yet ethics and PII protection are not. The right stance is both appreciative and skeptical: appreciative of Moini’s clear, practitioner‑friendly guidance, and skeptical enough to insist that we overlay her three points with robust, documented safeguards rooted in the ABA Model Rules. Use AI, ground it in your documents, and choose tasks wisely—but do so as a lawyer first and a technologist second. Above all, review your work, stay relentlessly wary of the terms that govern your tools, and treat PII and client confidences as if a bar investigator were reading over your shoulder. In this era, one might be. ⚖️🤖🔐

MTC