MTC (Bonus): National Court Technology Rules: Finding Balance Between Guidance and Flexibility ⚖️

/Standardizing Tech Guidelines in the Legal System

Lawyers and their staff needs to know the standard and local rules of AI USe in the courtroom - their license could depend on it.

The legal profession stands at a critical juncture where technological capability has far outpaced judicial guidance. Nicole Black's recent commentary on the fragmented approach to technology regulation in our courts identifies a genuine problem—one that demands serious consideration from both proponents of modernization and cautious skeptics alike.

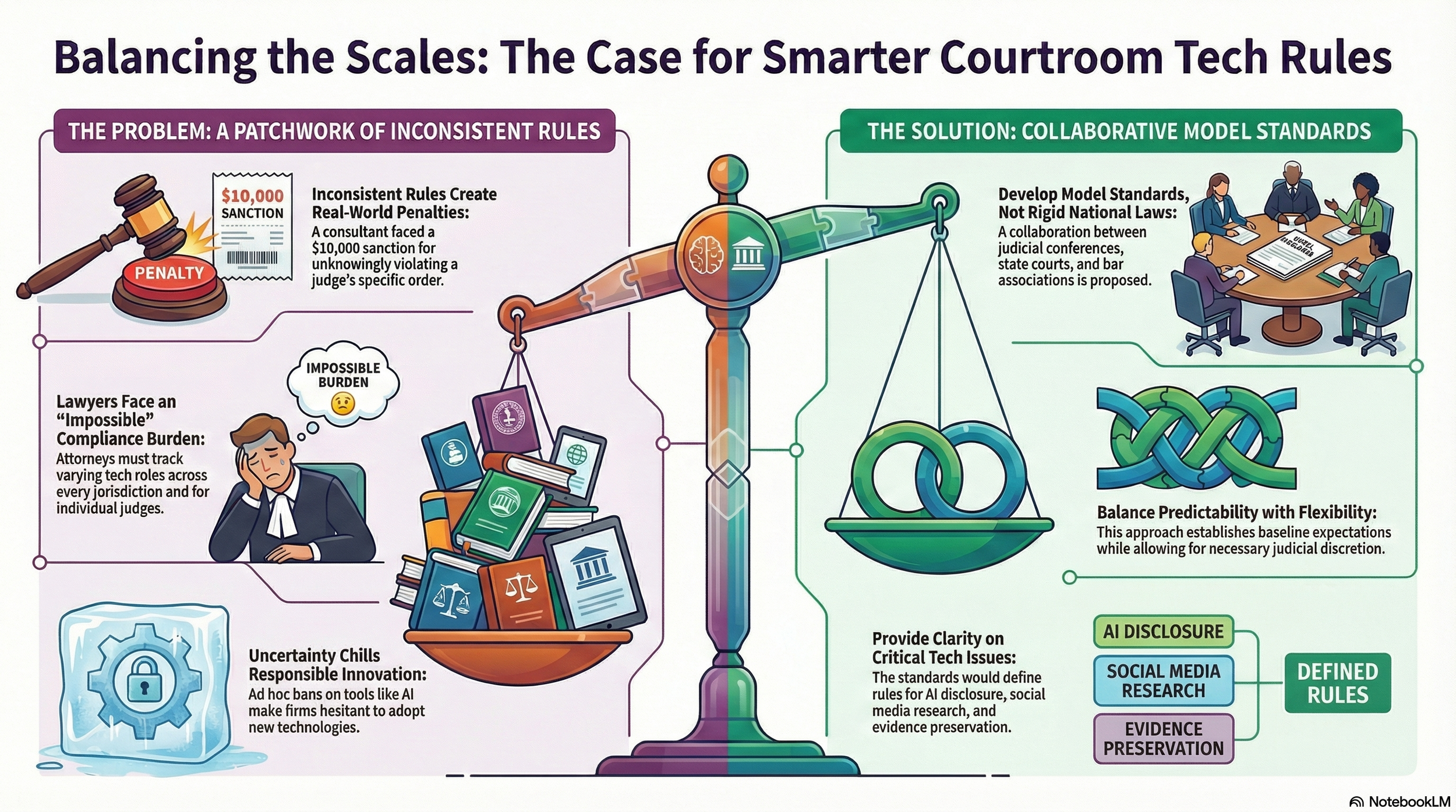

The core tension is understandable. Courts face legitimate concerns about technology misuse. The LinkedIn juror research incident in Judge Orrick's courtroom illustrates real risks: a consultant unknowingly violated a standing order, resulting in a $10,000 sanction despite the attorney's good-faith disclosure and remedial efforts. These aren't theoretical concerns—they reflect actual ethical boundaries that protect litigants and preserve judicial integrity. Yet the response to these concerns has created its own problems.

The current patchwork system places practicing attorneys in an impossible position. A lawyer handling cases across multiple federal districts cannot reasonably track the varying restrictions on artificial intelligence disclosure, social media evidence protocols, and digital research methodologies. When the safe harbor is simply avoiding technology altogether, the profession loses genuine opportunities to enhance accuracy and efficiency. Generative AI's citation hallucinations justify judicial scrutiny, but the ad hoc response by individual judges—ranging from simple guidance to outright bans—creates unpredictability that chills responsible innovation.

SHould there be an international standard for ai use in the courtroom

There are legitimate reasons to resist uniform national rules. Local courts understand their communities and case management needs better than distant regulatory bodies. A one-size-fits-all approach might impose burdensome requirements on rural jurisdictions with fewer tech-savvy practitioners. Furthermore, rapid technological evolution could render national rules obsolete within months, whereas individual judges retain flexibility to respond quickly to emerging problems.

Conversely, the current decentralized approach creates serious friction. The 2006 amendments to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for electronically stored information succeeded partly because they established predictability across jurisdictions. Lawyers knew what preservation obligations applied regardless of venue. That uniformity enabled the profession to invest in training, software, and processes. Today's lawyers lack that certainty. Practitioners must maintain contact lists tracking individual judge orders, and smaller firms simply cannot sustain this administrative burden.

The answer likely lies between extremes. Rather than comprehensive national legislation, the profession would benefit from model standards developed collaboratively by the Federal Judicial Conference, state supreme courts, and bar associations. These guidelines could allow reasonable judicial discretion while establishing baseline expectations—defining when AI disclosure is mandatory, clarifying which social media research constitutes impermissible contact, and specifying preservation protocols that protect evidence without paralyzing litigation.

Such an approach acknowledges both legitimate judicial concerns and legitimate professional needs. It recognizes that judges require authority to protect courtroom procedures while recognizing that lawyers require predictability to serve clients effectively.

I basically agree with Nicole: The question is not whether courts should govern technology use. They must. The question is whether they govern wisely—with sufficient uniformity to enable compliance, sufficient flexibility to address local concerns, and sufficient clarity to encourage rather than discourage responsible innovation.