HOW TO: How Lawyers Can Protect Themselves on LinkedIn from New Phishing 🎣 Scams!

/Fake LinkedIn warnings target lawyers!

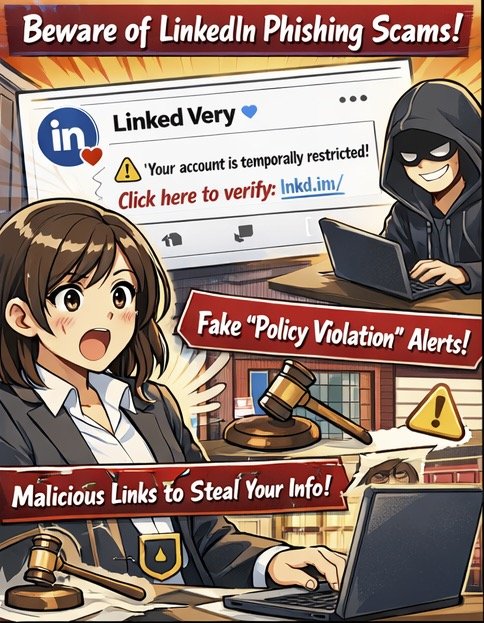

LinkedIn has become an essential networking tool for lawyers, making it a high‑value target for sophisticated phishing campaigns.⚖️ Recent scams use fake “policy violation” comments that mimic LinkedIn’s branding and even leverage the official lnkd.in URL shortener to trick users into clicking on malicious links. For legal professionals handling confidential client information, falling victim to one of these attacks can create both security and ethical problems.

First, understand how this specific scam works.💻 Attackers create LinkedIn‑themed profiles and company pages (for example, “Linked Very”) that use the LinkedIn logo and post “reply” comments on your content, claiming your account is “temporarily restricted” for non‑compliance with platform rules. The comment urges you to click a link to “verify your identity,” which leads to a phishing site that harvests your LinkedIn credentials. Some links use non‑LinkedIn domains, such as .app, or redirect through lnkd.in, making visual inspection harder.

To protect yourself, treat all public “policy violation” comments as inherently suspect.🔍 LinkedIn has confirmed it does not communicate policy violations through public comments, so any such message should be considered a red flag. Instead of clicking, navigate directly to LinkedIn in your browser or app, check your notifications and security settings, and only interact with alerts that appear within your authenticated session. If the comment uses a shortened link, hover over it (on desktop) to preview the destination, or simply refuse to click and report it.

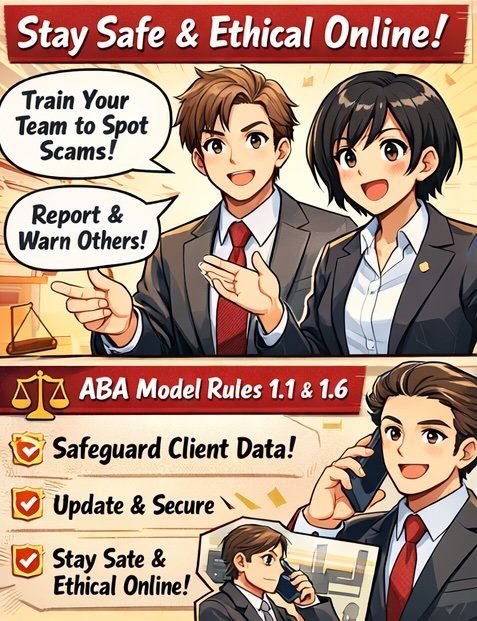

From an ethics standpoint, these scams directly implicate your duties under ABA Model Rules 1.1 and 1.6.⚖️ Comment 8 to Rule 1.1 stresses that competent representation includes understanding the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology. Failing to use basic safeguards on a platform where you communicate with clients and colleagues can fall short of that standard. Likewise, Rule 1.6 requires reasonable efforts to prevent unauthorized access to client information, which includes preventing account takeover that could expose your messages, contacts, or confidential discussions.

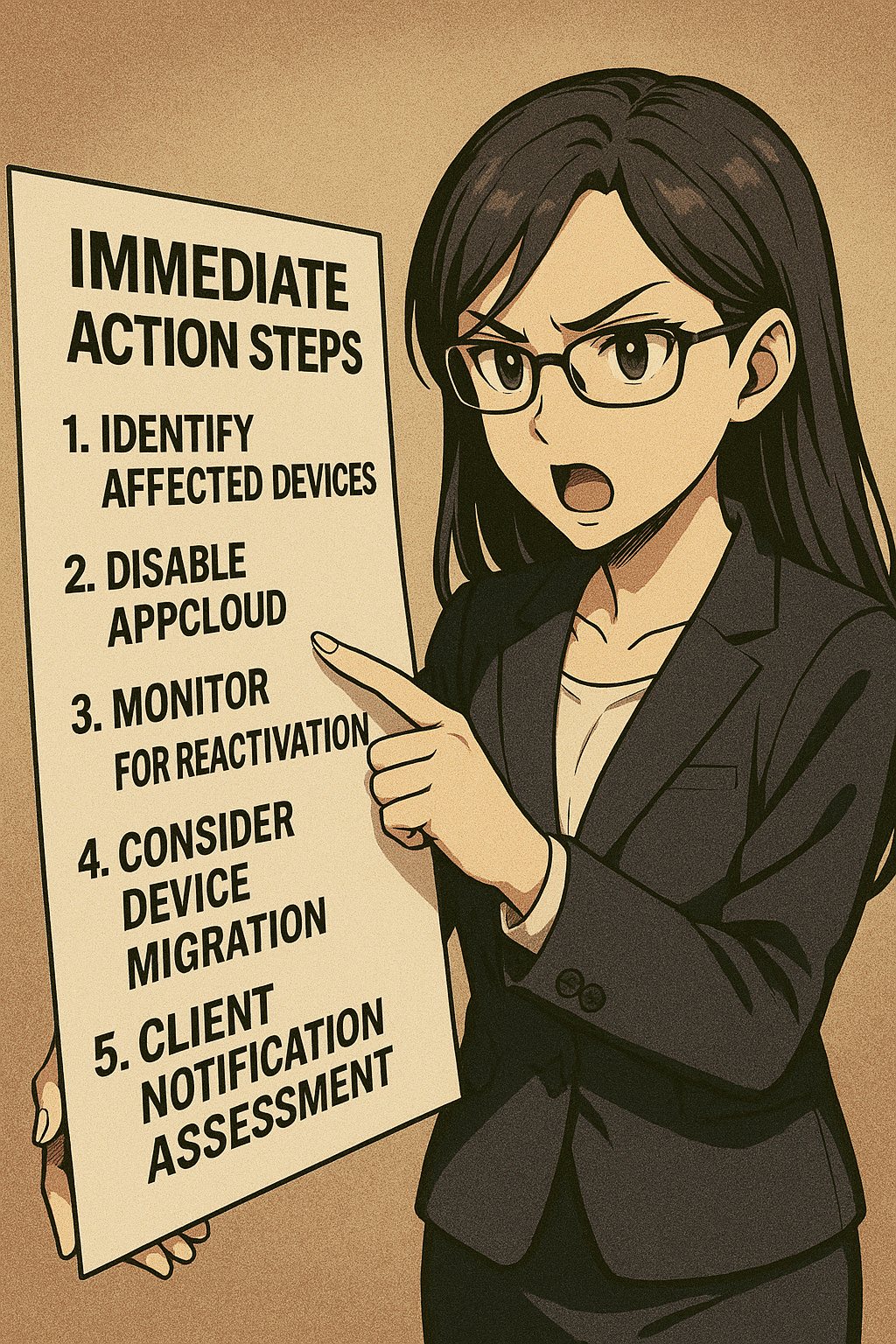

Practically, you should enable multi‑factor authentication (MFA) on LinkedIn, use a unique, strong password stored in a reputable password manager, and review active sessions regularly for unfamiliar devices or locations.🔐 If you suspect you clicked a malicious link, immediately change your LinkedIn password, revoke active sessions, enable or confirm MFA, and run updated anti‑malware on your device. Then notify your firm’s IT or security contact and consider whether any client‑related disclosures are required under your jurisdiction’s ethics rules and breach‑notification laws.

Finally, build a culture of security awareness in your practice.👥 Brief colleagues and staff about this specific comment‑reply scam, show screenshots, and explain that LinkedIn does not resolve “policy violations” via comment threads. Encourage a “pause before you click” mindset and make reporting easy—internally to your IT team and externally to LinkedIn’s abuse channels. Taking these steps not only protects your professional identity but also demonstrates the technological competence and confidentiality safeguards the ABA Model Rules expect from modern legal practitioners.

Public “policy violations” are a red flag!

From an ethics standpoint, these scams directly implicate your duties under ABA Model Rules 1.1 and 1.6.⚖️ Comment 8 to Rule 1.1 stresses that competent representation includes understanding the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology. Failing to use basic safeguards on a platform where you communicate with clients and colleagues can fall short of that standard. Likewise, Rule 1.6 requires reasonable efforts to prevent unauthorized access to client information, which includes preventing account takeover that could expose your messages, contacts, or confidential discussions.

Practically, you should enable multi‑factor authentication (MFA) on LinkedIn, use a unique, strong password stored in a reputable password manager, and review active sessions regularly for unfamiliar devices or locations.🔐 If you suspect you clicked a malicious link, immediately change your LinkedIn password, revoke active sessions, enable or confirm MFA, and run updated anti‑malware on your device. Then notify your firm’s IT or security contact and consider whether any client‑related disclosures are required under your jurisdiction’s ethics rules and breach‑notification laws.

Train your team to pause and report!

Finally, build a culture of security awareness in your practice.👥 Brief colleagues and staff about this specific comment‑reply scam, show screenshots, and explain that LinkedIn does not resolve “policy violations” via comment threads. Encourage a “pause before you click” mindset and make reporting easy—internally to your IT team and externally to LinkedIn’s abuse channels. Taking these steps not only protects your professional identity but also demonstrates the technological competence and confidentiality safeguards the ABA Model Rules expect from modern legal practitioners.