MTC: Everyday Tech, Extraordinary Evidence: How Lawyers Can Turn Smartphones, Dash Cams, and Wearables Into Case‑Winning Proof After the Minnesota ICE Shooting 📱⚖️

/Smartphone evidence: Phone as Proof!

The recent fatal shooting of ICU nurse Alex Pretti by a federal immigration officer in Minneapolis has become a defining example of how everyday technology can reshape a high‑stakes legal narrative. 📹 Federal officials claimed Pretti “brandished” a weapon, yet layered cellphone videos from bystanders, later analyzed by major news outlets, appear to show an officer disarming him moments before multiple shots were fired while he was already on the ground. In a world where such encounters are documented from multiple angles, lawyers who ignore ubiquitous tech risk missing powerful, and sometimes exonerating, evidence.

Smartphones: The New Star Witness

In the Minneapolis shooting, multiple smartphone videos captured the encounter from different perspectives, and a visual analysis highlighted discrepancies between official statements and what appears on camera. One video reportedly shows an officer reaching into Pretti’s waistband, emerging with a handgun, and then, barely a second later, shots erupt as he lies prone on the sidewalk, still being fired upon. For litigators, this is not just news; it is a case study in how to treat smartphones as critical evidentiary tools, not afterthoughts.

Practical ways to leverage smartphone evidence include:

Identifying and preserving bystander footage early through public calls, client outreach, and subpoenas to platforms when appropriate.

Synchronizing multiple clips to create a unified timeline, revealing who did what, when, and from where.

Using frame‑by‑frame analysis to test or challenge claims about “brandishing,” “aggressive resistance,” or imminent threat, as occurred in the Pretti shooting controversy.

In civil rights, criminal defense, and personal‑injury practice, this kind of video can undercut self‑defense narratives, corroborate witness accounts, or demonstrate excessive force, all using tech your clients already carry every day. 📲

GPS Data and Location Trails: Quiet but Powerful Proof

The same smartphones that record video also log location data, which can quietly become as important as any eyewitness. Modern phones can provide time‑stamped GPS histories that help confirm where a client was, how long they stayed, and in some instances approximate movement speed—details that matter in shootings, traffic collisions, and kidnapping cases. Lawyers increasingly use this location data to:

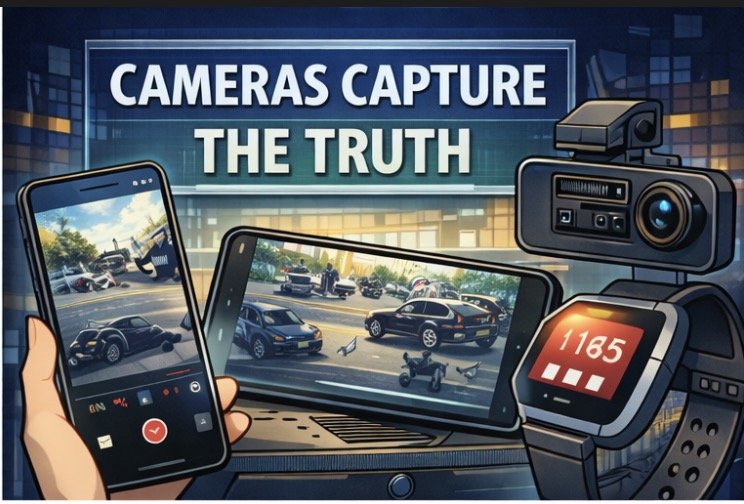

Dash cam / cameras: Dashcam Truth!

Corroborate or challenge alibis by matching GPS trails with claimed timelines.

Reconstruct movement patterns in protest‑related incidents, showing whether someone approached officers or was simply present, as contested in the Minneapolis shooting narrative.

Support or refute claims that a vehicle was fleeing, chasing, or unlawfully following another party.

In complex matters with multiple parties, cross‑referencing GPS from several phones, plus vehicle telematics, can create a robust, data‑driven reconstruction that a fact‑finder can understand without a computer science degree.

Dash Cams and 360‑Degree Vehicle Video: Replaying the Scene

Cars now function as rolling surveillance systems. Many new vehicles ship with factory cameras, and after‑market 360‑degree dash‑cam systems are increasingly common, capturing impacts, near‑misses, and police encounters in real time. In a Minneapolis‑style protest environment, vehicle‑mounted cameras can document:

How a crowd formed, whether officers announced commands, and whether a driver accelerated or braked before an alleged assault.

The precise position of pedestrians or officers relative to a car at the time of a contested shooting.

Sound cues (shouts of “he’s got a gun!” or “where’s the gun?”) that provide crucial context to the video, like those reportedly heard in footage of the Pretti shooting.

For injury and civil rights litigators, requesting dash‑cam footage from all involved vehicles—clients, third parties, and law‑enforcement—should now be standard practice. 🚗 A single 360‑degree recording might capture the angle that police‑worn cameras miss or omit.

Wearables and Smartwatches: Biometrics as Evidence

GPS & wearables: Data Tells All!

Smartwatches and fitness trackers add a new dimension: heart‑rate, step counts, sleep data, and sometimes even blood‑oxygen metrics. In use‑of‑force incidents or violent encounters, this information can be unusually persuasive. Imagine:

A heart‑rate spike precisely at the time of an assault, followed by a sustained elevation that reinforces trauma testimony.

Step‑count and GPS data confirming that a client was running away, standing still, or immobilized as claimed.

Sleep‑pattern disruptions and activity changes supporting damages in emotional‑distress claims.

These devices effectively turn the body into a sensor network. When combined with phone video and location data, they help lawyers build narratives supported by objective, machine‑created logs rather than only human recollection. ⌚

Creative Strategies for Integrating Everyday Tech

To move from concept to courtroom, lawyers should adopt a deliberate strategy for everyday tech evidence:

Build intake questions that explicitly ask about phones, car cameras, smartwatches, home doorbell cameras, and even cloud backups.

Move quickly for preservation orders, as Minnesota officials did when a judge issued a temporary restraining order to prevent alteration or removal of shooting‑related evidence in the Pretti case.

Partner with reputable digital‑forensics professionals who can extract, authenticate, and, when needed, recover deleted or damaged files.

Prepare demonstrative exhibits that overlay video, GPS points, and timelines in a simple visual, so judges and juries understand the story without technical jargon.

The Pretti shooting also underscores the need to anticipate competing narratives: federal officials asserted he posed a threat, while video and witness accounts cast doubt on that framing, fueling protests and calls for accountability. Lawyers on all sides must learn to dissect everyday tech evidence critically—scrutinizing what it shows, what it omits, and how it fits with other proof.

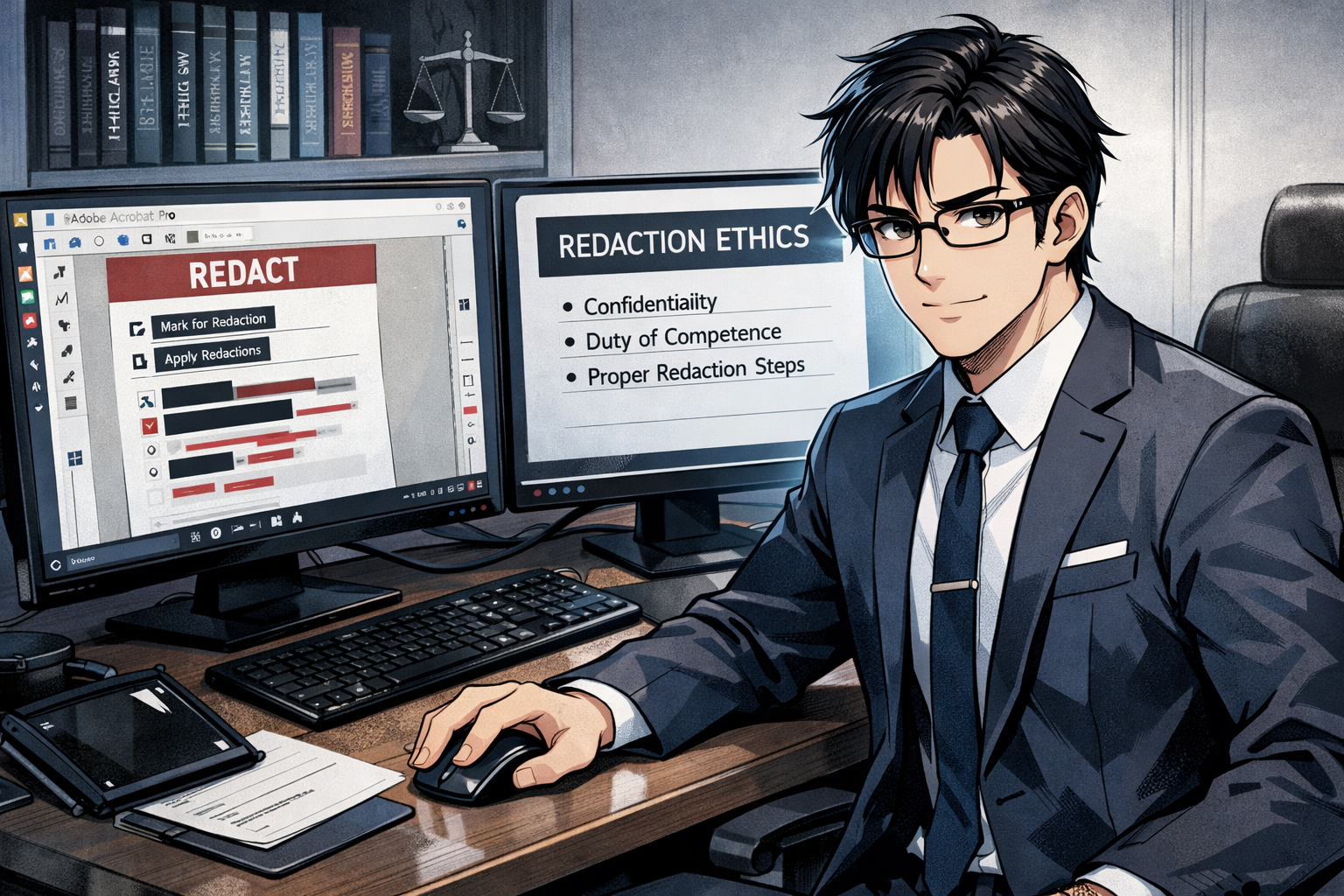

Ethical and Practical Guardrails

Ethics-focused image: Ethics First!

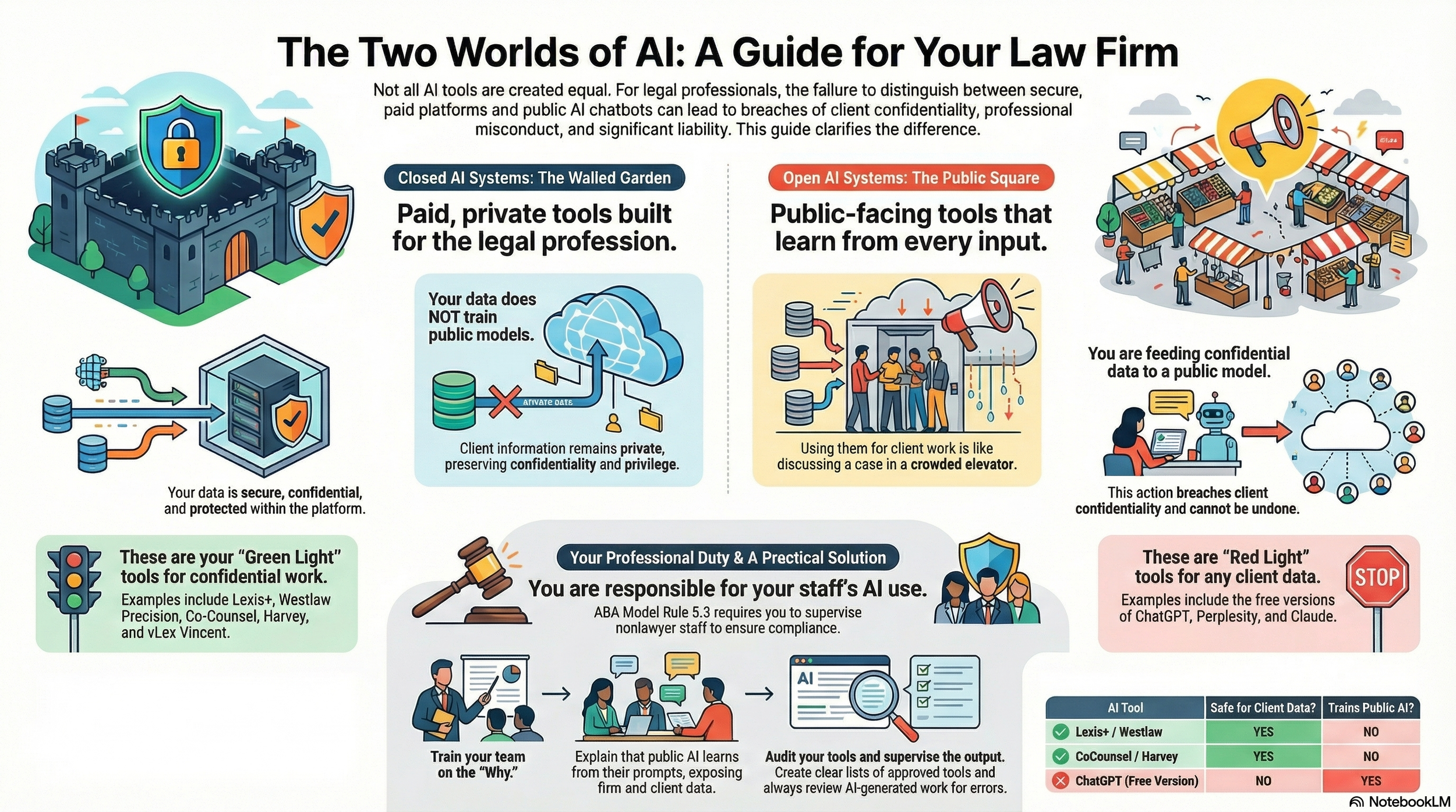

With this power comes real ethical responsibility. Lawyers must align their use of everyday tech with core duties under the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct.

Competence (ABA Model Rule 1.1)

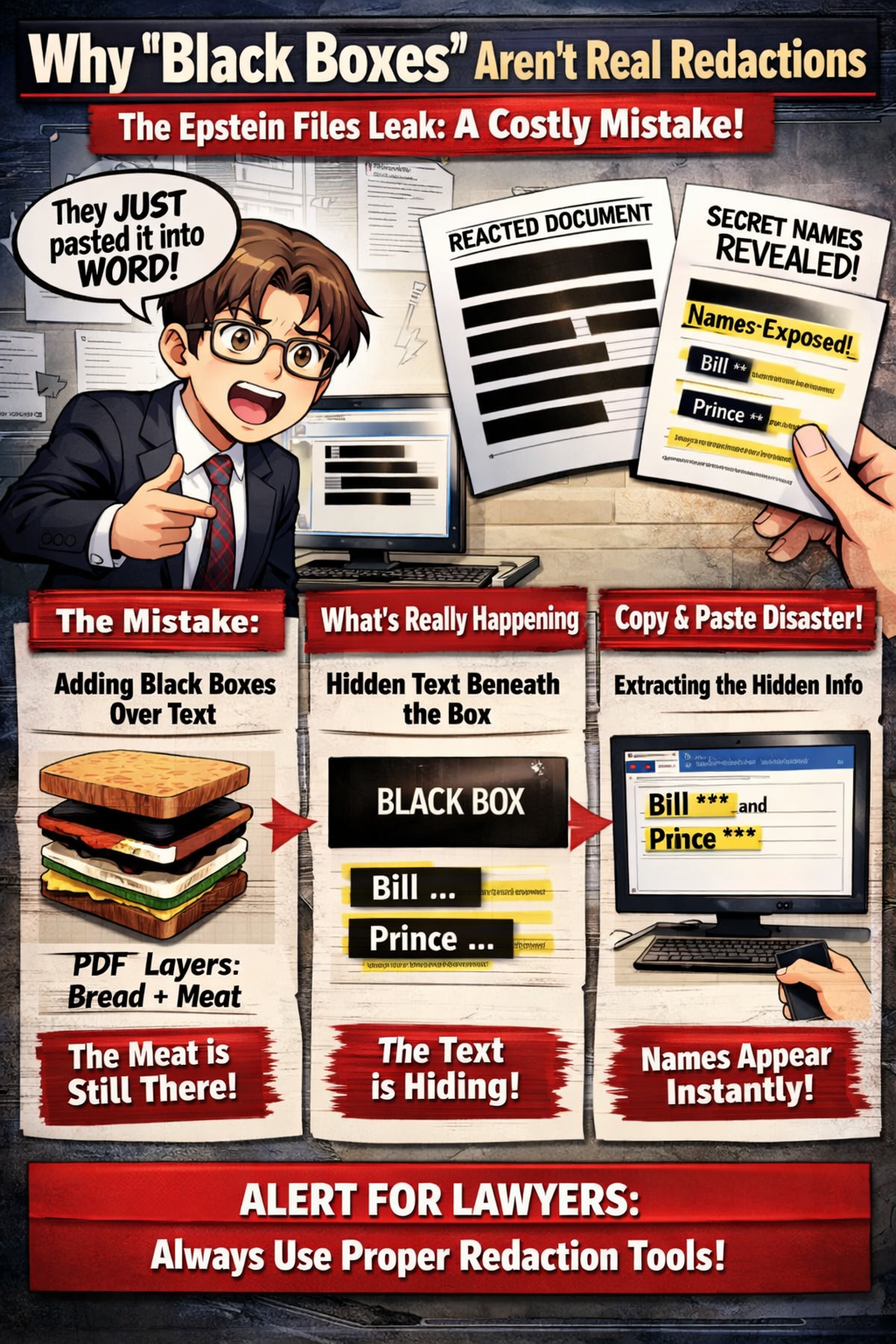

Rule 1.1 requires “competent representation,” and Comment 8 now expressly includes a duty to keep abreast of the benefits and risks of relevant technology. When you rely on smartphone video, GPS logs, or wearable data, you must either develop sufficient understanding yourself or associate with or consult someone who does.Confidentiality and Data Security (ABA Model Rule 1.6)

Rule 1.6 obligates lawyers to make reasonable efforts to prevent unauthorized access to or disclosure of client information. This extends to sensitive video, location trails, and biometric data stored on phones, cloud accounts, or third‑party platforms. Lawyers should use secure storage, limit access, and, where appropriate, obtain informed consent about how such data will be used and shared.Preservation and Integrity of Evidence (ABA Model Rules 3.4, 4.1, and related e‑discovery ethics)

ABA ethics guidance and case law emphasize that lawyers must not unlawfully alter, destroy, or conceal evidence. That means clients should be instructed not to edit, trim, or “clean up” recordings, and that any forensic work should follow accepted chain‑of‑custody protocols.Candor and Avoiding Cherry‑Picking (ABA Model Rule 3.3, 4.1)

Rule 3.3 requires candor toward the tribunal, and Rule 4.1 prohibits knowingly making false statements of fact. Lawyers should present digital evidence in context, avoiding selective clips that distort timing, perspective, or sound. A holistic, transparent approach builds credibility and protects both the client and the profession.Respect for Privacy and Non‑Clients (ABA Model Rule 4.4 and related guidance)

Rule 4.4 governs respect for the rights of third parties, including their privacy interests. When you obtain bystander footage or data from non‑clients, you should consider minimizing unnecessary exposure of their identities and, where feasible, seek consent or redact sensitive information.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Handled with these rules in mind, everyday tech can reduce factual ambiguity and support more just outcomes. Misused, it can undermine trust, compromise admissibility, and trigger disciplinary scrutiny. ⚖️